Can individualized therapy cure breast cancer?

At the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB, at Stuttgart, Germany, biochips are being trialed in an attempt to estimate the best, personalized therapy for mammary carcinoma.

Breast cancer is considered the most widespread form of cancer in women in industrialized countries. About one in every nine women will suffer from breast cancer during her life. The reasons why the cancer develops may be very different. For about five percent of all cases a hereditary cause has been demonstrated; among the remaining sufferers, the actual mechanisms underlying the cancer’s development are largely still unknown. As yet, therefore, there exists no one form of therapy which is equally successful in all those affected.

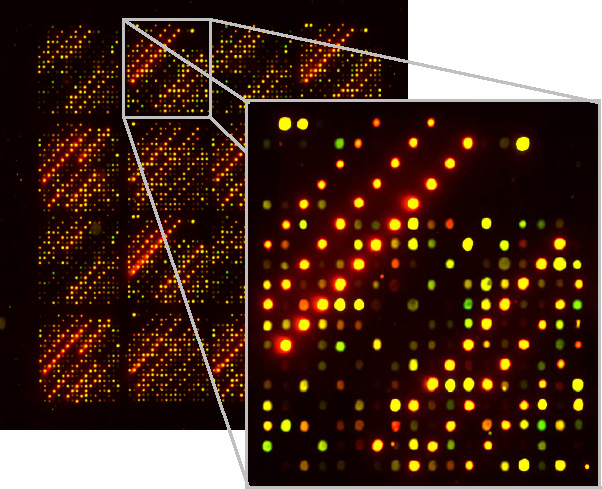

The diagnosis at present generally first entails feeling for lumps in the breast, which are then investigated further by imaging techniques such as mammography. If cancer is still suspected after that, the tissue is surgically removed and analyzed. The reasons for the growth of tumors are very varied; for example, they may lie in the pathological overexpression of growth factor genes. Knowing the cause in each individual case is therefore fundamental for the doctor treating the tumor, in order to be able to decide on the right therapy. Doctors urgently need a differentiated diagnosis in order to estimate beforehand the treatment method that offers the best chance of a cure. One appropriate way of achieving this may be to investigate the tumors using biochips.

In an integrated research project sponsored by the fund of the German state of Baden-Württemberg, and in cooperation with the Robert Bosch Hospital, Stuttgart, and the German Universities of Tübingen and Stuttgart, the Fraunhofer IGB has been developing, since midway through 2002, a biochip for improved, individualized breast cancer diagnosis. Using this chip, several hundred selected gene sections are quickly and reliably screened to classify mammary carcinomas within a single analysis. “The biochip is currently being tested on material from clinical samples. These results will help determine the best therapeutic approach on a personalized basis,” says Nicole Hauser, project leader in the IGB’s “Genomics, Proteomics, Screening” group.

To start with, the biochips were developed using established breast cancer cell lines. Since the beginning of the research project, over a hundred mammary carcinomas have been collected in a tissue bank at the Robert Bosch Hospital. These carcinomas are being progressively analyzed using the test biochip. The analyses produce what are called gene expression profiles of tumors, one of whose uses is to develop bioinformatics techniques for predicting the clinical course of a cancerous disease.

“The major difference between this and previous studies is that, rather than using a non-specific biochip, we have put together a selected number of genes. This concentrates the analysis on genes relevant to breast cancer, which in contrast to whole-genome biochips allows for inexpensive, focused production and hence a future spread of this technology to all patients,” explains Nicole Hauser. The developments have been shepherded by partner firms with an interest in the future utilization and marketing of this specific biochip technology. In the case of successful application, it is possible that the technology may be extended to cover other kinds of tumor, such as colonic carcinomas, for example.

Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB

Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB